My Life in Pictures

Beginnings

When I was growing up, Harry (dad) was the family shutterbug. He had an Eastman Kodak brownie camera that took two-and-a quarter inch square photos and was his most precious possession. In fact, no one else in the family would have ever considered touching it—not Kitty (mom), nor either of my two older sisters (Deedee or Patti), nor I. In fact, when he wasn’t actually taking photos, he carefully guarded his camera (along with his Playboy magazines), in the bottom of his wardrobe, under lock and key.

We were a working-class family living in a working-class Manhattan neighborhood, on the 4th floor of a 6-story apartment building that was right across the street from the 207th street elevated stop on the 7th avenue (IRT) line. Dad’s parents, Bertha and Benny, immigrated to NYC with their families as teenagers, from a town in the Ukraine known as Chernigova. Every summer they rented a bungalow for us in the Rockaways, a few blocks from the beach. Dad worked in the city during the week but every Friday afternoon he would take the A-train to our stop at 44th Street and Rockaway Beach Boulevard.

I am 2 years old (L) here with a friend, my 6 year-old sister, Patti, 10 year-old sister Deedee, and cousin Susie (R).

My fondest memories are those I spent swimming in the ocean with mom. She was a strong, confident and beautiful swimmer with a long, graceful stroke, which she learned by watching Johnny Weissmuller (Tarzan) and Esther Williams (Jane) in the movies. With me perched on her back holding onto her bathing suit straps, she would swim far out to sea, a long way past where the jetties ended and the waves would break. Dad captured us riding the waves into shore. I was just 5 years old.

After I went off to college, dad moved to Florida with his second family, leaving behind all the photos he took of us. Mom stayed in NYC. After mom passed away—her ashes scattered at sea by the armed services (she had been a WAC during WWII)—Deedee became the keeper of the photos, negatives and all, which over the years had been crammed into a black-and-white marbled photo box and several old shoe boxes. She sent me armfuls of photos and handed off the negatives to cousin Grace who offered to digitize them. None of us can remember what happened to Dad’s brownie camera.

I got my first camera when I was 19 years old. It was a brand new 35 mm Konica given to me by my mom’s Haitian boyfriend, Michel. Without even opening the box, I traded it in for a Pentax “Spotmatic.” I took my very first picture of the northbound train that followed the Hudson River. It was wintertime; the tracks and the branches of the trees alongside the tracks were snow-covered.

In 1973, Russ Nichols, the soon-to-be first husband of a friend of mine, gave me a quick lesson in basic darkroom techniques—developing b&w film and printing—in a three-hour session at Goucher College. Russ was a filmmaker, (an Olympic canoeist), and a perfectionist, so I learned pretty good habits.

I transferred to Cornell University and after graduating I worked as a lab assistant in Animal Cytogenetics for Professor Stephen Bloom. One of my tasks was to make photo enlargements of the mutations in 4-day old chick embryo chromosomes which I had exposed to various chemicals (food dyes, pesticides, and anti-cancer agents), as part of Bloom’s ongoing mutagenesis research. On weekends, Bloom let me use the darkroom for my own photos. That’s when I discovered Cibachrome—a positive-to-positive process using color transparencies (in my case, Kodachrome 64 and Ektachrome 100) to make color prints. Cibachrome’s intensity, color saturation and luminosity were absolutely thrilling. Of course, the subject matter helped too. My first color prints were of red Trillium—with its rich, blood-red colored petals that signaled springtime in the forests and woodlands around Ithaca—and of the Great Spangled Fritillary—a gorgeous orange, yellow and rust-colored butterfly with black bars and white polka dots.

In 1978, my best friend, Steve Lapointe and I decided to apply to be Peace Corps volunteers. We were given the choice of going either to Afghanistan or Honduras. We were leaning toward Afghanistan which seemed more interesting culturally (and more dramatic visually), even though it was also known to be rather repressive for women. We met a lovely couple in Ithaca who had lived in Afghanistan for several years, and after spending an evening with them, we were psyched. Then the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and Peace Corps pulled out its volunteers. At that point, our choices were either Honduras or Liberia. We chose Honduras, thinking that learning Spanish would be a good skill to have. As it turned out, both Afghanistan and Honduras were dangerous places. The former had a war, while Honduras had a military dictatorship supported by U.S. corporations and our government.

We were sent first to La Guácima, Alajuela, Costa Rica for 10 weeks to learn Spanish and tropical agriculture. After training, we were transferred to our site—a town called Tocoa, beyond Standard Fruit Company’s banana and African palm plantations, and far from the Caribbean sea. It was a frontier town where all the men who were “men,” carried machetes. Saloons were everywhere; bar fights and gunfire were common occurrences. No one had running water, indoor toilets or electricity. A few of the homes we were invited to had television sets, but of course, no electrical outlets to plug them into. The heat was really quite remarkable. It was so hot that the candles melted even when they were unlit. This was the tropics after all.

In the rainy season, the roads in and out of Tocoa were impassable. The air strip was a goat field. The only planes that could fly in were DC-3’s and they had to make a pass or two over the field to scare off the goats and clear it for landing. The Honduran airlines—LAHSA and SAHSA—flew from Tegucigalpa (the capital), to San Pedro Sula, to La Ceiba, then to Tocoa. We used to joke that SAHSA was the acronym for Stay At Home Stay Alive. (Portfolio 2).

Our new home consisted of one-half of a cement block structure. The other half was occupied by a lovely young woman and her gun-toting, pistol-whipping husband. The house had a cement floor and screens on the windows. Our water supply was the river, a mile and a half away. On our first day there, we hired a couple of kids with a wheel barrow and several buckets to fetch water from the river and fill a 55-gallon steel drum we had acquired and kept in the backyard. We hired a man to cut a path to the outhouse, also in the backyard. In the process, he killed three coral snakes, which have very potent and deadly venom. We worried about a lot of things besides poisonous snakes while living in Tocoa—stray (and not-so-stray) bullets, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and mosquitos carrying malaria and dengue fever.

To get to the central school (and its satellite schools) where we worked with teachers and kids—digging a well, planting vegetable gardens and papaya trees, and raising rabbits, bees, chickens and pigs—we rode heavy, black clunker bikes called Flying Pigeons, which had been imported from China. At the end of the day, we would return “home” absolutely drenched with sweat. Before settling in for the evening, we would venture into the backyard to the “shower” where we would pour buckets of water over each other from the drum.

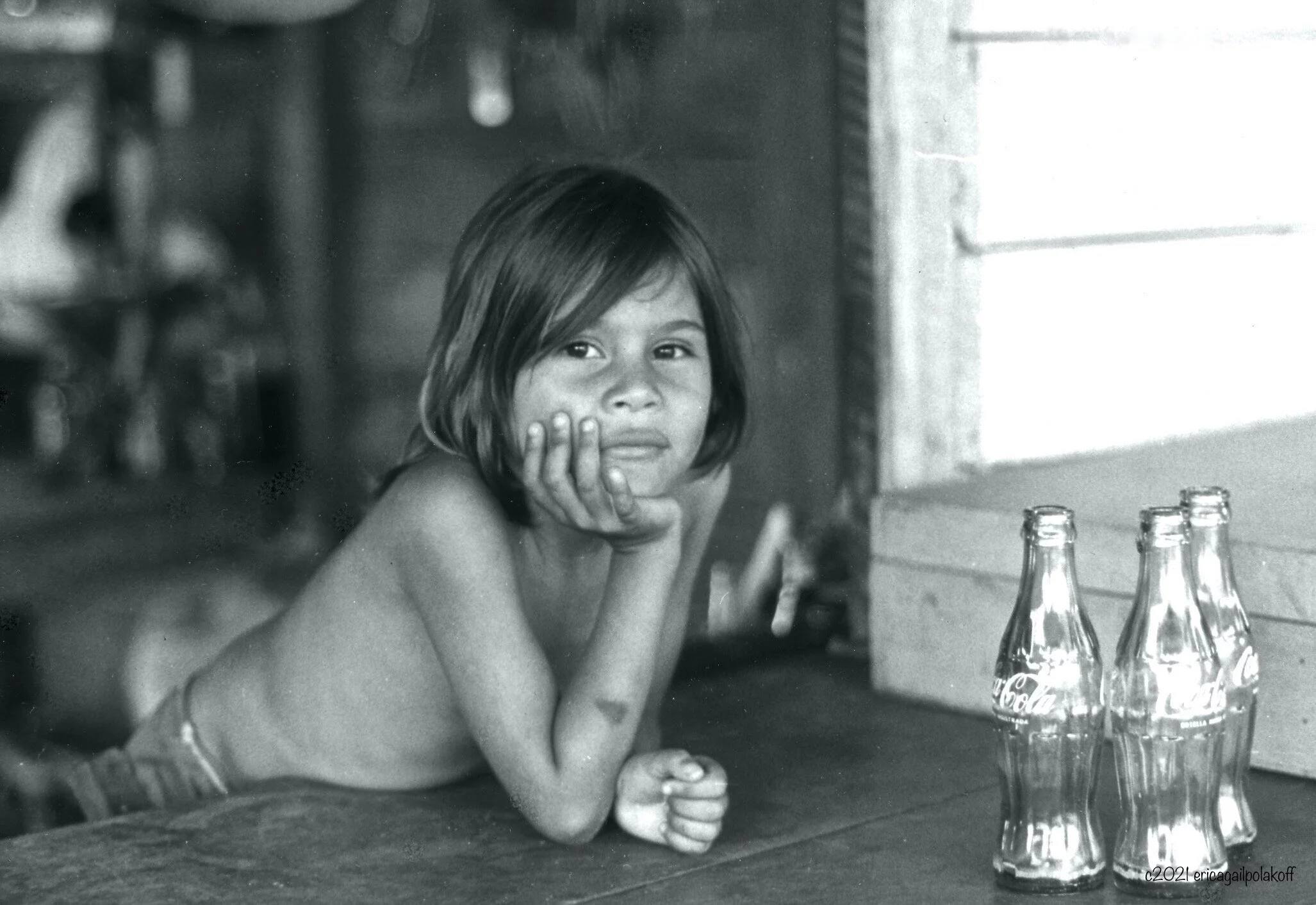

I had always been drawn to b&w photography, and I was (and forever will be) in awe of how Ansel Adams could make mountains appear as though they were lit from the inside out. However, I hadn’t yet found myself in a place where the landscapes demanded to be seen in black-and-white. In Tocoa, my focus was people, particularly the kids we worked with in the schools (Portfolio 2). This is AlmaOndina, one of eight kids who lived next door with their mom. From the window ledge of the front room of their home, they sold mostly warm Coca Colas. The year was 1978.

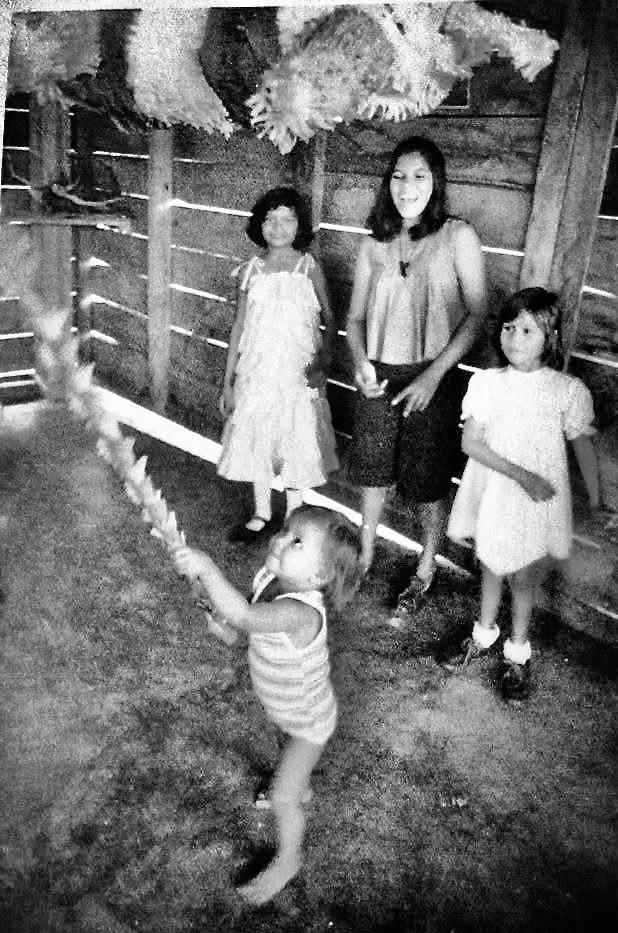

This is Sandra—the youngest of the kids next door having her turn at the piñata Steve and I made for them.

During our stint in the Peace Corps, we had a chance to visit Guatemala, trekking to Chichicastenango, Panajachel on Lake Atitlán, and Antigua (Portfolio 3). We also visited the Honduran island of Roatán to snorkel in the blue Caribbean Sea. Oh! how I wished I had an underwater camera. The life on the reef was simply astounding—manta rays, barracudas, sea turtles, schools of blue tangs, lion fishes, sea anemones and every color and shape of coral. My fascination with the sea and my respect for its inhabitants have always been with me and evolved photographically into what I have called “Synecdoche” (Portfolio 1) and “Fish” and No-Fish” (Portfolio 3).

On July 19, 1979, the Sandinistas defeated the 43-year Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua. As things were heating up in the neighboring countries—El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—we were sent to Costa Rica, this time for several weeks, to assist in the training of the next group of volunteers, many of whom would remain in Costa Rica, although a few were sent on to Honduras. Several years later, I would return to Nicaragua to study the revolution from the ground up, photographing the conditions of life, particularly in the squatter settlements. (Portfolio 1)

In any case, our Peace Corps experience led us back to Ithaca and to graduate school at Cornell University, where Steve studied entomology and I studied sociology with concentrations in Women’s Studies and Latin American Studies.

Becoming “The Photographer”

“A photograph is not a rendering, an imitation or interpretation of its subject but actually a trace of it. No painting or drawing no matter how naturalist, belongs to its subject in the way that a photograph does…

We can only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice. As a result of this act, we see what is brought within our reach. We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Our vision is continually moving; continually holding things in a circle around itself, constituting what is present to ourselves as we are.” (John Berger)

During the summer of 1982, I went to Bolivia for the first time. The following year, I received a Fulbright doctoral dissertation grant to carry out research in Bolivia for one year (1983-84). I returned a third time for the month of January 1985.

How and why I chose Bolivia is a rather complicated story. As a graduate student at Cornell, I was drawn to Andean history, and indigenous language (Quechua) and culture. I fell in love with José Maria Arguedas’ Deep Rivers, a novel based on the author’s childhood in the mountains and valleys of Peru, which he wrote in Spanish and Quechua, the latter for which he suffered a great deal of criticism from the Peruvian literary elites. I was fortunate to have had the opportunity to know Frances Barraclough, who lived and worked in Ithaca, and translated the work into English, preserving the Quechua passages. Her sensibilities seemed to perfectly match Arguedas’; she had me enthralled with Quechua—its poetry, cadence and complexity.

I was also studying “Andean Systems of Production” with anthropologist Billie Jean Isbell. The course involved analyzing data that had been collected in three small villages in Bolivia, for a project on household economies that had been organized by U.S. AID (Agency for International Development). Reading about the daily lives of campesinos (“peasants,” and in Bolivia, mostly indigenous peoples) and how they somehow managed to survive unrelenting social, economic and political chaos, against a backdrop of very high, snow-covered peaks and lush valleys, sparked my interest and captured my imagination. That first summer, I just tried to absorb it all. It was fairly early on in the following year that I became “The Photographer.”

I had been living in the Cochabamba valley for about four months in 1983, when Florinda, a young peasant woman whom I was getting to know rather well, asked me if I had a camera and if I would photograph her cousin’s wedding in her village, Curba Ciega (Blind Curve), which had a population of about 100 people. The wedding was a simple, traditional wedding in an old stone and clay church in the village. Florinda was very pleased with the photos. She selected the ones she wanted copies of for her family and her cousin’s. She seemed so very happy and said her cousin would be thrilled!

After that, word spread quickly, and soon I had dozens of requests to photograph people—at work in the markets, in the slaughterhouses, in their homes, in the chicherías where chicha (an alcoholic beverage made from fermented corn) was brewed and served; at birthdays, saints’ days and celebrations. In Florinda’s quiet and unassuming way, she got me started making b&w portraits of people, and it is because of her that I became known as “The Photographer.” In fact, if I wasn’t carrying my camera and taking pictures, I was reprimanded for not doing my job, by most of the people I knew.

And so, I used the camera to discover different lives and rhythms, different values and beliefs, and in this way, not only did I learn more about the people with whom I lived and worked but also I learned more about myself. I found connections between my life and theirs and these connections generated an intimacy which I think is reflected in their portraits. (Portfolio 1)

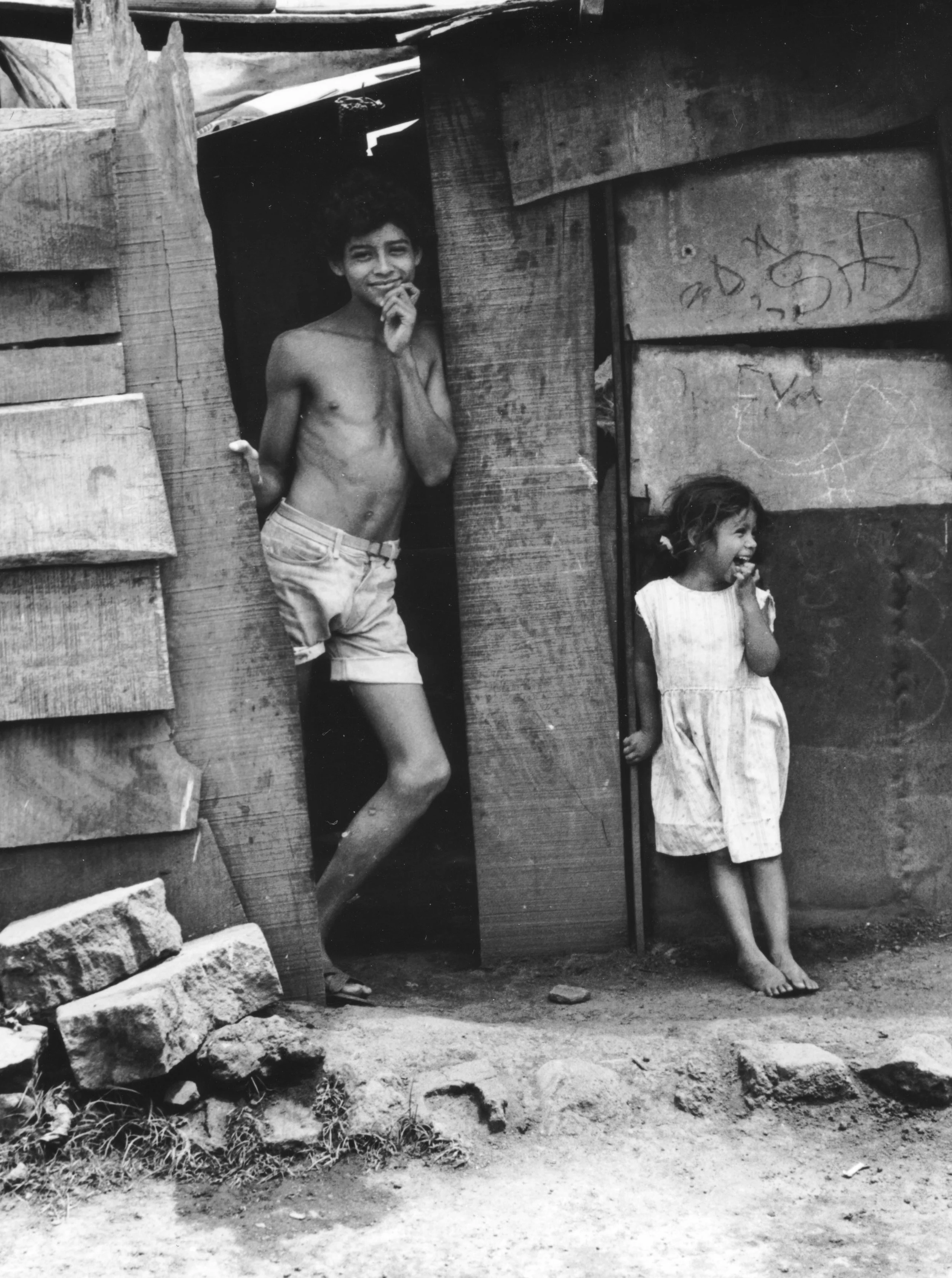

Throughout the year, in addition to making portraits for individuals, I was asked by two organizations to serve as their photographer. For CUSO, a Canadian development organization similar to the Peace Corps, I documented a number of projects that they supported in the mining communities of the highlands. For CERES (Center for the Study of the Social and Economic Reality), a Bolivian social science research organization, I documented three projects, two of which they published as monographs. The first was called La Mina Urbana (the Urban Mine); it was about Jaihuayco, a brick-making community on the outskirts of Cochabamba. The second was about the central market in the city of Cochabamba known as La Cancha. The last was about Plan Tres Mil, a resettlement community south of the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. The community was named Plan 3,000 for the number of migrants for whom it was created. However, more than 30,000 people settled there, most of whom were illegal squatters, living under very precarious conditions. (Portfolios 1 & 3)

In September 1984, I returned to Ithaca and Cornell University, and with the good graces of my fairy godmother or godfather (whose identity was never revealed to me), was awarded a fellowship for the year, in order to finish my dissertation. I also received a grant from the Latin American Studies Program to mount an exhibit of my photos. But first I had to convince a professor in Cornell’s School of Art & Architecture to take me on as an independent study student so that I could gain access to the School’s 24-hour darkrooms. Barry Perlus, a newly minted Assistant Professor of Photography, became my mentor. Under his guidance, I learned to experiment with developers and different grades of papers. I also learned dodging and burning-in techniques, how to make archival prints and b&w positives (slides), matting and framing and mounting an exhibit.

And so, I spent hours on end in the darkroom, day after day, listening to the music of the Kjarkas (a Bolivian band playing traditional melodies on traditional instruments that reverberated with the soul of the Andes), immersed in the magic of bringing to life, images of the people I had known. People who had somehow survived the chaos and unrest of that period in Bolivia’s social history; people who had opened up their hearts and their homes to me and made me feel like I belonged. I wanted to write their story which had become so deeply and indelibly etched in mine. At the time, I didn’t realize I wouldn’t be ready to write that story for another 40 years.

I have recently completed the first draft of a manuscript about Bolivia in the 1980’s, based on my experiences living there. It is illustrated with many of the images that are currently in my portfolio, and hopefully it will be launched into cyberspace by the end of September 2025. The book is entitled UNREST.

NICARAGUA

After Bolivia, my attention turned to Nicaragua. The Sandinista victory in 1979, over the corrupt and brutal Somoza dictatorship—a regime that had been supported by the U.S. government for decades—was unprecedented. During the late 1970s, as a Peace Corps volunteer in Honduras, I had witnessed the complicity of the United States in backing a violent military dictatorship. And, it was well-known that the U.S. government had sided not only with the Honduran military government, but also with the Somoza regime and other dictatorships throughout Latin America.

I spent the mid-1980s through the early 1990s, photographing the conditions in the squatter settlements in Nicaragua (especially in Managua, León, Estelí, and Masaya) which had arisen since the Sandinista Triumph, and with my best friend and collaborator, Pierre LaRamée, interviewing their residents. We also interviewed the leaders of several grassroots organizations—neighborhood associations and women’s organizations, in particular—that were created both during the struggle and after 1979. We met so many extraordinary young people who were committed to the revolutionary process and democracy—people who faced insurmountable odds and powerful opposition both internally and externally, who continued to struggle and fight for justice and freedom from oppression.

Almost all of the photos I shot during those years were in b&w (Plus-X). A number were later published in sociology journals as photoessays. (Portfolio 1)

VISUAL SOCIOLOGY

Between 1986 and 2006, I created courses in “Visual Sociology” at several different colleges and universities including Hobart & William Smith Colleges (Geneva, NY), St. Lawrence University (Canton, NY) and Bloomfield College (Bloomfield, NJ). An emerging discipline in the 80s, visual sociology is based on the idea that the world we see and create around us says something about who we are as a society and culture; and, it is essential to understand how our “visual” world and all of the images with which we are bombarded, affect us as human beings.

At each school, I managed to scrounge together the resources to make a workable darkroom so that I could teach the students basic darkroom techniques for the photography projects they were required to produce for the course. This was especially the case at Bloomfield College. The director of our media services, a good friend and colleague, Barbara Isacson donated a camera and darkroom equipment (including an enlarger) that had belonged to her late father, Harry Isacson, who had been a photographer. Another colleague of mine, Professor of Physics, Dave Kilbourne, donated equipment and his actual darkroom, which was adjacent to his physics lab and office. Dave often ate his lunch in his office and took a great interest in the photos the students were producing. He would even pop in and occasionally help out. The President of the College, Jack Noonan, provided a grant so that I could buy a third enlarger and chemicals. Each week I scheduled two 4-hour shifts of six students each, sharing three enlargers. It was always a bit chaotic at first. But inevitably, a few of the students would catch on quickly and could help teach those who were having difficulties, so that by mid-semester, we were pretty well-organized.

Their first assignment in “Visual Sociology” was to create an ad campaign, with multiple photographs that they had taken themselves, for something specific—an actual object or a thing (like a place), or an idea (like the notion of tranquility), or an emotion (like compassion)—without ever using the word or the thing itself. A second project was to photograph their world—its interior as well as its exterior. The third was an ethnographic project—on a culture or subculture that they found interesting. Since quite a few of our students were born in other countries—many from Latin American and Caribbean cultures—but grew up in the US, this project gave them a chance to learn more about their heritage. Part of the assignment was to interview members of the group they chose and to allow their subjects to guide them on what to photograph. Their final project was to produce a photoessay or slide show with sound accompaniment, on “the self without the self.” That is, they had to photograph who they were without using any images of themselves. The students definitely produced an interesting and unique body of work.

In 2006, the Chair of the Division of Creative Arts and Technology, jazz musician, bass player and good friend, Chris White, invited me to teach the Division’s first course in “An Introduction to B&W Photography” for the students in his Division, during an intensive summer session. Interest was really high but since the darkroom could only accommodate 12 students, I had to turn away so many students. I spent all the money I earned teaching that course to buy my first digital camera— a CANON EOS-5D.

GOING DIGITAL

Learning to use the Canon EOS-5D was a project in itself. First of all, there were many new functions to experiment with. The ability to change the ISO between shots (the ISO correlates to the ASA or film speed of a whole roll of film), gave added flexibility for different lighting environments and effects. The range was so much greater than what I had been accustomed to. Likewise for the shutter speed and F-stop. That was just the beginning. Perhaps most amazing was that I could release the shutter, get immediate feedback and make adjustments (provided the subject was not fleeting). And, I didn’t have to mix chemicals or breathe them in. What I missed, however, was watching the images magically appear in the developing process, and the serenity and sense of freedom and purpose I felt while working—the darkness of the darkroom, lit only by a single red safe light, had been totally enveloping, and interestingly, somehow comforting. Very quickly, picture-taking became a virtually new experience.

With the change in process and style of working came a change in subject matter. I started “playing” much more—experimenting with many of the functions/possibilities that digital technology allowed. My work started to take a different direction as I ventured into the realm of abstraction. “Synecdoche” (in Portfolio 1 ) is an example of one “offshoot.” (Synecdoche is a part of speech wherein a single element of the whole represents the whole, or vice versa.) I spent several weeks photographing tropical fish (photoshoots) in different locations—mostly in tropical fish stores in South Florida where I could get up close. Then in the “offshoot,” digitally focusing on an element of a particular fish, cropping and enlarging that element, and shifting the colors of the element and its background. (This was in sharp contrast to my previous film project of photographing larger sea creatures in aquaria around the country—Coney Island, South Jersey, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Key West, Mystic and Norwalk Connecticut, Baltimore, Boston (See: “FISH” and “NO-FISH” in Portfolio 3). As I mentioned early on, the sea and the miracle of water would appear and reappear over the years.

CUBA

It has always been a dream of mine to visit Cuba and in 2014, I had the opportunity to go twice (in June and November) for two weeks at a time. President Obama had finally opened relations with Cuba which had been suffering from a U.S. economic embargo under all previous administrations since 1961. For both trips, I joined groups organized by The Center for Global Studies which is based in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. The first tour focused on health and education; the second on organic and cooperative farms. Our “home base” was the Martin Luther King Jr. Center in Havana, but we traveled to locations south and east, visiting the Bay of Pigs Museum, schools, markets, medical centers, cultural institutes, conservation areas and farms. We attended lectures by scholars at every stop, had a chance to engage in discussions with everyday people, and took lots of photos (Slide show in Portfolio 1).

CAPE COD

Every springtime since 2005, my husband, our two dogs and I have made the trek out to Cape Cod for a couple of weeks after our college’s graduation. Since retiring from teaching, we have been going twice a year—in the fall as well as the spring—the two best times of the year. We all love the Cape, especially our dogs (both past and present). They frolic on the great expanses of empty beaches where they can run free and chase each other forever and ever; splashing through the water, keeping an eye on the seals and gulls, contemplating sunrises and sunsets. They are truly at their happiest (See “Happy Dogs” in Portfolio 2). I too, love the seemingly endless expanses—of sand, ocean and sky—the miraculous blues of the water below and the heavens above (azure, cobalt, turquoise, midnight, powder, cerulean, lapis, sapphire, indigo, Prussian), the greens of the sea and marshes (teal, emerald, sea, moss, pine, chartreuse, juniper, olive, fern, basil, sage, lime, etc.), the tans of the shore (sand, gold, caramel, orange and brown), and glorious sunrises and sunsets (surprising us with pinks, violets, tangerine, burnt orange, and fiery reds)—all of which present endless photographic possibilities. Every day the light is different—changing with the ever-changing cloud cover, angle of the sun, and moisture in the air. (See all Cape Cod series in Portfolios 1 &2).